There are places and people who aim to develop the culture of freedom and human rights. These places and people work based on the accounts of ordinary people, not heroes. They preserve the memory of human nature, which is not always perfect or even good, but they work for our better future.

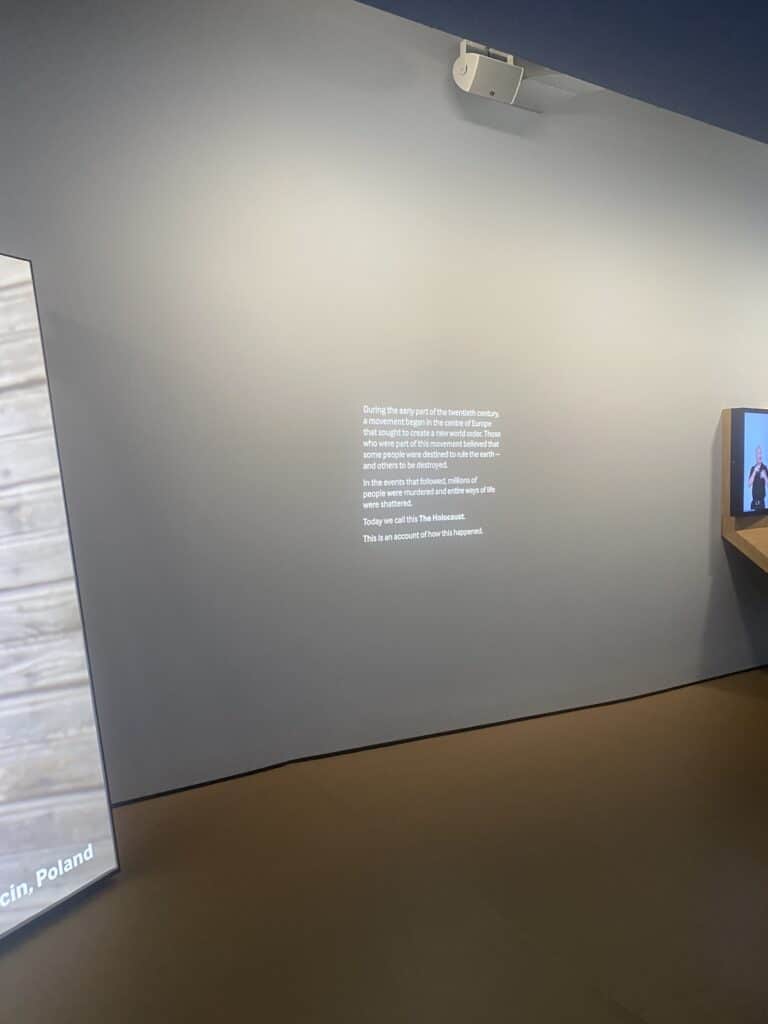

As a researcher in the field of memory politics, my interests are concentrated in two countries – Poland and the USA, but I am sometimes in other places, like London. Having visited there, I can say that there is a special place on the map of places of remembrance in London. It is the Imperial War Museum. It may seem that the main purpose of the museum is to explore war, but that is a partial truth.

Spread over six floors, the museum has a vast collection of objects – from uniforms to vehicles to weapons to film – each with a story to tell. The IWM London is the world’s leading museum of war. Founded during World War I, it gives voice to the extraordinary experiences of ordinary people who were forced to live their lives in a world torn apart by conflict. Their voices are important not only because they were survivors and witnesses. It is also thanks to the research of such first-hand testimonies that we have been able to reconstruct most of the events of the past.

I believe that such voices, which the Museum has been collecting since the First War, were particularly important at the beginning of its creation – given the lack of professional institutions concerned with the protection of human rights and military tribunals.

War has long been seen as a means of showing who is in the right in the eyes of the conflict. Diplomacy, which prevents wars, developed slowly. Its roots can be traced to the Treaty of Versailles, but it did not develop until the 20th century.

The cruelty and ruthlessness of World War II in the heart of civilized Europe led to deep shock and a desire to punish those responsible for refusing peace. In 1948, the term genocide was added to the law (Rudawski 2014, 305-317). Only then did the United Nations General Assembly adopt the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (Nijakowski 2012, 30). The law has opened the door to progress in the defense of human rights, but the task is not over, because every day there are examples of human rights violations around the world. By this I mean not only the war in Ukraine, but also what happened in Burma or Syria. Nowadays, it is easier to monitor what is happening in the world in terms of human rights violations, thanks to legal provisions, governmental and non-governmental organizations.

The U.S. in particular, through sociopolitical mechanisms, even though it has been accused of not ratifying all treaties in support of human rights (Pastusiak 2018), has a tremendous track record of monitoring genocides and violence, negotiating peace agreements, and preventing conflicts from developing. The main state institution working to protect human rights and fight anti-Semitism, intolerance, and xenophobia is the USHMM. I have written a lot about the USHMM (see, for example, here), but now I am trying to present activities similar to those of the USHMM organization in Europe. The inspiration for this comes from the film War Crimes, with Investigators in Ukraine by Marie-Laure and Widmer Baggiolini.

Thanks to the work of the Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights, the film can be seen in Poland. We do not know when the war in Ukraine will end, but undoubtedly the International Criminal Court will have enough evidence to indict Russian war crimes – promises the organization. As we can learn from the film, this will be possible thanks to the detailed work of the staff of the European organization. What are they doing? Well, they collect evidence – and film it. They also look for witnesses and interview them. What we hear from these interviews is horrific. The witnesses make shocking statements. They are collected by the filmmakers not only to preserve their memories, but also to provide justice.

This is what happens at the end of the exhibition about the Holocaust in the museum in London. Today, thanks to people and organizations, everyone knows this story, but the survivors’ testimonies are the most valuable report. Because it is only thanks to personal stories that we can put ourselves in the shoes of a victim and, as the USHMM teaches, start our own work to prevent future human rights violations. It would not have been possible if there were not constant memorials, museums, organizations, and people collecting evidence. They all use their power to record what they have seen and heard.

Bibliography:

- Marie-Laure and Widmer Baggiolini, War Crimes, with Investigators in Ukraine, Szwajcaria 2022.

- Nijakowski, L. M., Pojęcie ludobójstwa: definicje, propaganda i walki symboliczne [in:] Auschwitz a zbrodnie ludobójstwa XX wieku, A. Bartuś, P. Trojański (eds.) Oświęcim, Państwowe Muzeum Auschwitz-Birkanau, 2012.

- Pastusiak, L., Prawa człowieka w polityce Stanów Zjednoczonych, „Przegląd Dziennikarski”, 15.05. 2018.

- Rudawski B., Czym jest Zagłada dla historyka?, „Ethics in Progress”, 2014, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 305–317.

- The Imperial War Museum, London

- The Holocaust, Permanent exhibition (PE) of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM), description of PE is based on author’s visit to the museum financed by a subsidy of the Faculty of International and Political Studies of Jagiellonian University for research activities.

- The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), Paris, December 10, 1948.